Untangling the Mysteries of Knots with Quantum Computers

What Quantum Advantage actually looks like

By Konstantinos Meichanetzidis

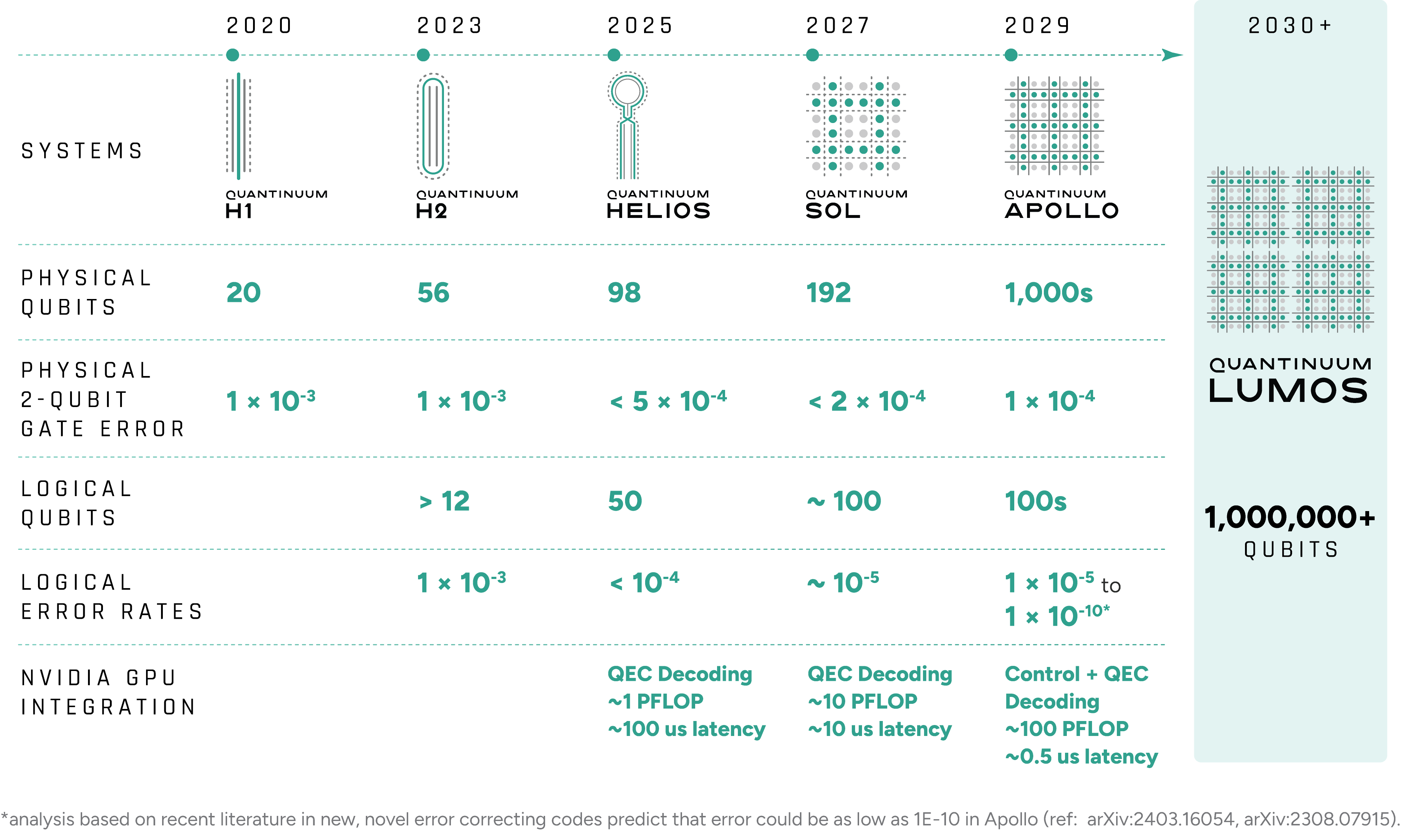

One of the greatest privileges of working directly with the world’s most powerful quantum computer at Quantinuum is building meaningful experiments that convert theory into practice. The privilege becomes even more compelling when considering that our current quantum processor – our H2 system – will soon be enhanced by Helios, a quantum computer potentially a stunning trillion times more powerful, and due for launch in just a few months. The moment has now arrived when we can build a timeline for applications that quantum computing professionals have anticipated for decades and which are experimentally supported.

Quantinuum’s applied algorithms team has released an end-to-end implementation of a quantum algorithm to solve a central problem in knot theory. Along with an efficiently verifiable benchmark for quantum processors, it allows for concrete resource estimates for quantum advantage in the near-term. The research team, included Quantinuum researchers Enrico Rinaldi, Chris Self, Eli Chertkov, Matthew DeCross, David Hayes, Brian Neyenhuis, Marcello Benedetti, and Tuomas Laakkonen of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In this article, Konstantinos Meichanetzidis, a team leader from Quantinuum’s AI group who led the project, writes about the problem being addressed and how the team, adopting an aggressively practical mindset, quantified the resources required for quantum advantage:

Knot theory is a field of mathematics called ‘low-dimensional topology’, with a rich history, stemming from a wild idea proposed by Lord Kelvin, who conjectured that chemical elements are different knots formed by vortices in the aether. Of course, we know today that the aether theory was falsified by the Michelson-Morley experiment, but mathematicians have been classifying, tabulating, and studying knots ever since. Regarding applications, the pure mathematics of knots can find their way into cryptography, but knot theory is also intrinsically related to many aspects of the natural sciences. For example, it naturally shows up in certain spin models in statistical mechanics, when one studies thermodynamic quantities, and the magnetohydrodynamical properties of knotted magnetic fields on the surface of the sun are an important indicator of solar activity, to name a few examples. Remarkably, physical properties of knots are important in understanding the stability of macromolecular structures. This is highlighted by work of Cozzarelli and Sumners in the 1980’s, on the topology of DNA, particularly how it forms knots and supercoils. Their interdisciplinary research helped explain how enzymes untangle and manage DNA topology, crucial for replication and transcription, laying the foundation for using mathematical models to predict and manipulate DNA behavior, with broad implications in drug development and synthetic biology. Serendipitously, this work was carried out during the same decade as Richard Feynman, David Deutsch, and Yuri Manin formed the first ideas for a quantum computer.

Most importantly for our context, knot theory has fundamental connections to quantum computation, originally outlined by Witten’s work in topological quantum field theory, concerning spacetimes without any notion of distance but only shape. In fact, this connection formed the very motivation for attempting to build topological quantum computers, where anyons – exotic quasiparticles that live in two-dimensional materials – are braided to perform quantum gates. The relation between knot theory and quantum physics is the most beautiful and bizarre facts you have never heard of.

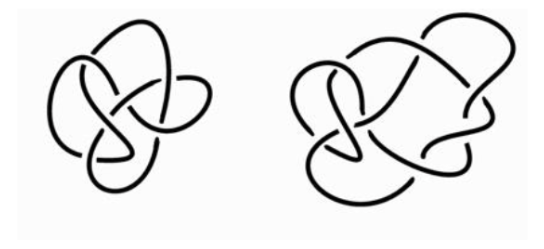

The fundamental problem in knot theory is distinguishing knots, or more generally, links. To this end, mathematicians have defined link invariants, which serve as ‘fingerprints’ of a link. As there are many equivalent representations of the same link, an invariant, by definition, is the same for all of them. If the invariant is different for two links then they are not equivalent. The specific invariant our team focused on is the Jones polynomial.

They all have the same Jones polynomial, as it is an invariant.

The mind-blowing fact here is that any quantum computation corresponds to evaluating the Jones polynomial of some link, as shown by the works of Freedman, Larsen, Kitaev, Wang, Shor, Arad, and Aharonov. It reveals that this abstract mathematical problem is truly quantum native. In particular, the problem our team tackled was estimating the value of the Jones polynomial at the 5th root of unity. This is a well-studied case due to its relation to the infamous Fibonacci anyons, whose braiding is capable of universal quantum computation.

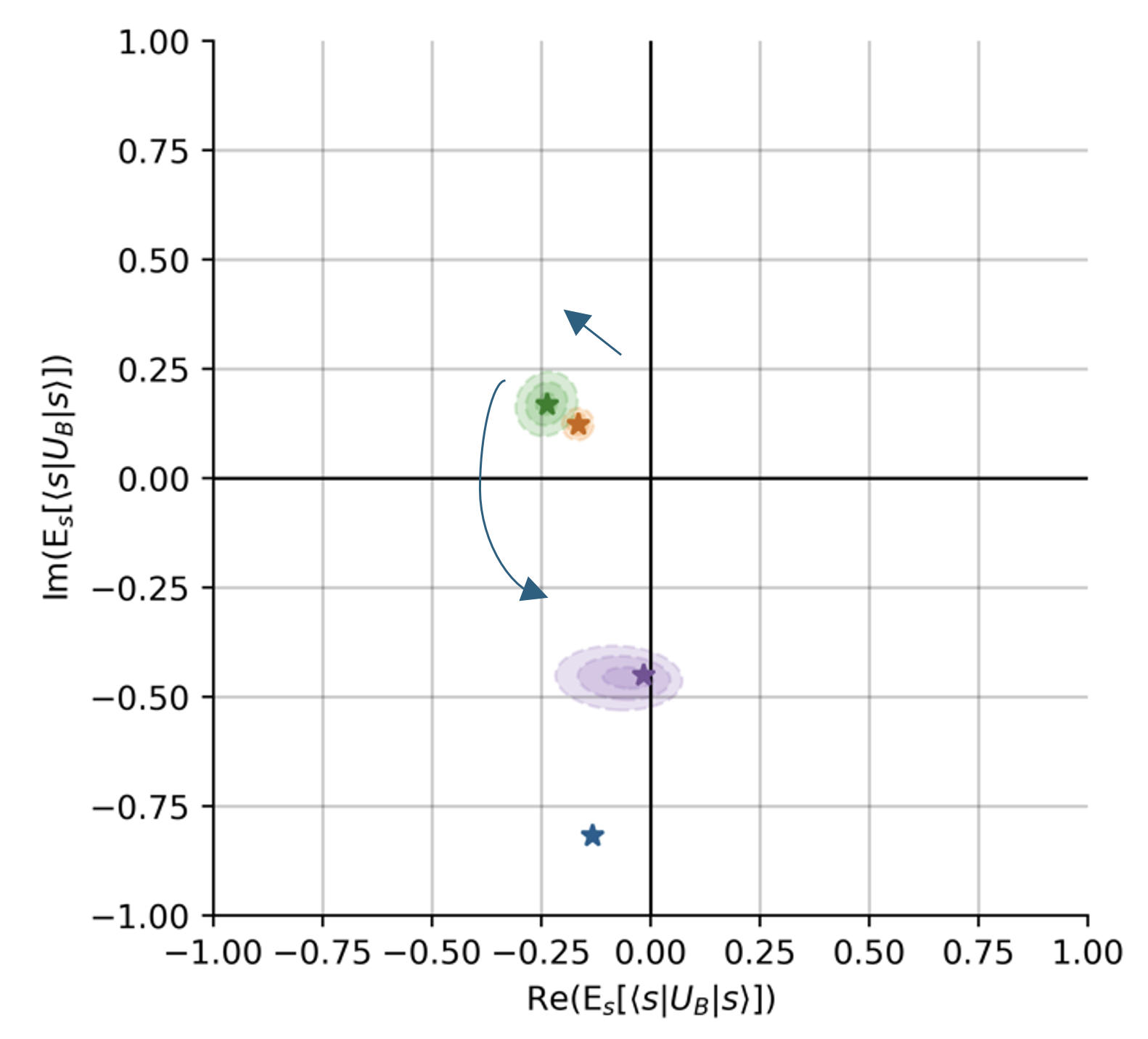

Building and improving on the work of Shor, Aharonov, Landau, Jones, and Kauffman, our team developed an efficient quantum algorithm that works end-to end. That is, given a link, it outputs a highly optimized quantum circuit that is readily executable on our processors and estimates the desired quantity. Furthermore, our team designed problem-tailored error detection and error mitigation strategies to achieve a higher accuracy.

In addition to providing a full pipeline for solving this problem, a major aspect of this work was to use the fact that the Jones polynomial is an invariant to introduce a benchmark for noisy quantum computers. Most importantly, this benchmark is efficiently verifiable, a rare property since for most applications, exponentially costly classical computations are necessary for verification. Given a link whose Jones polynomial is known, the benchmark constructs a large set of topologically equivalent links of varying sizes. In turn, these result in a set of circuits of varying numbers of qubits and gates, all of which should return the same answer. Thus, one can characterize the effect of noise present in a given quantum computer by quantifying the deviation of its output from the known result.

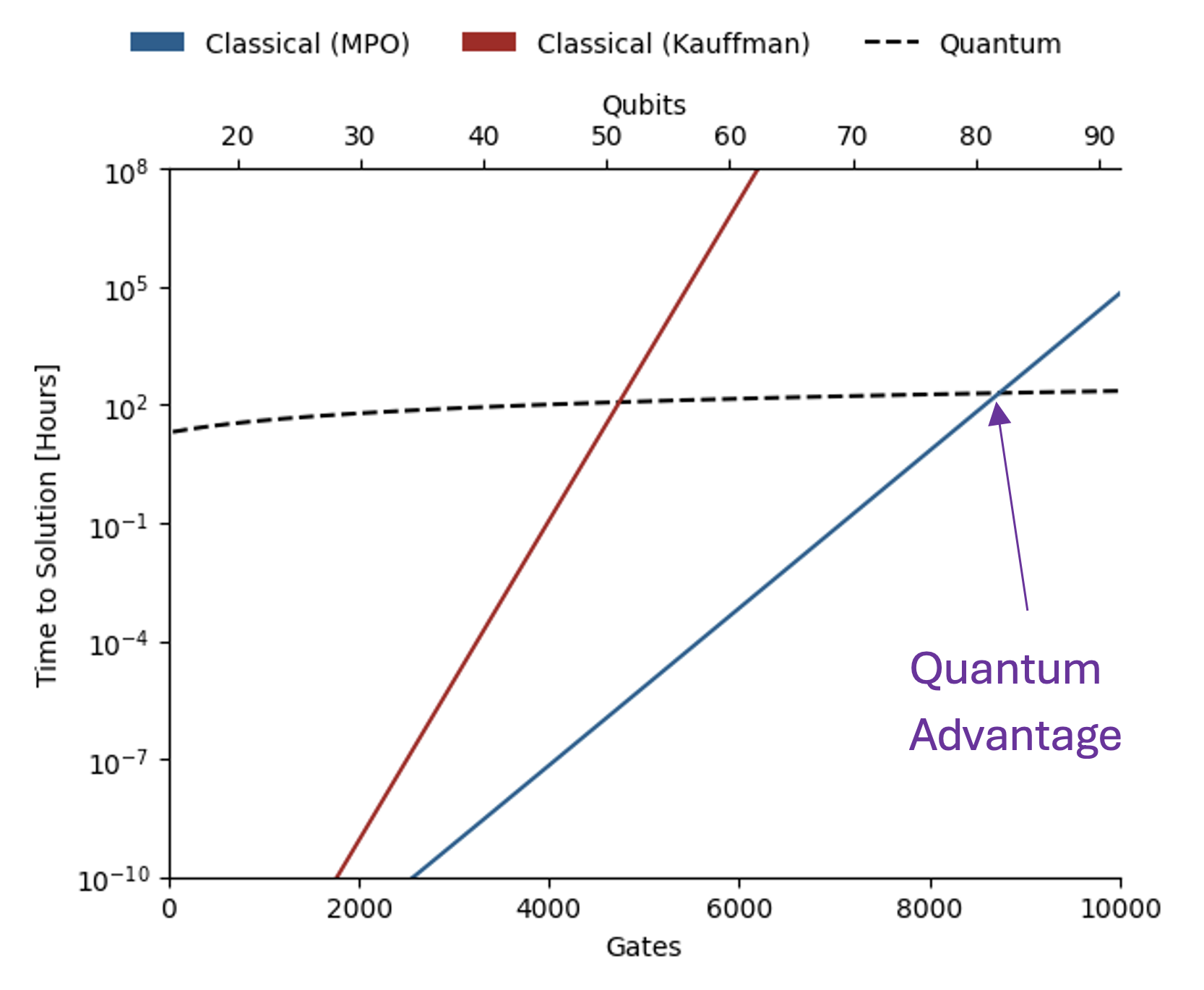

The benchmark introduced in this work allows one to identify the link sizes for which there is exponential quantum advantage in terms of time to solution against the state-of-the-art classical methods. These resource estimates indicate our next processor, Helios, with 96 qubits and at least 99.95% two-qubit gate-fidelity, is extremely close to meeting these requirements. Furthermore, Quantinuum’s hardware roadmap includes even more powerful machines that will come online by the end of the decade. Notably, an advantage in energy consumption emerges for even smaller link sizes. Meanwhile, our teams aim to continue reducing errors through improvements in both hardware and software, thereby moving deeper into quantum advantage territory.

The importance of this work, indeed the uniqueness of this work in the quantum computing sector, is its practical end-to-end approach. The advantage-hunting strategies introduced are transferable to other “quantum-easy classically-hard” problems. Our team’s efforts motivate shifting the focus toward specific problem instances rather than broad problem classes, promoting an engineering-oriented approach to identifying quantum advantage. This involves first carefully considering how quantum advantage should be defined and quantified, thereby setting a high standard for quantum advantage in scientific and mathematical domains. And thus, making sure we instill confidence in our customers and partners.

Edited

About Quantinuum

Quantinuum, the world’s largest integrated quantum company, pioneers powerful quantum computers and advanced software solutions. Quantinuum’s technology drives breakthroughs in materials discovery, cybersecurity, and next-gen quantum AI. With over 500 employees, including 370+ scientists and engineers, Quantinuum leads the quantum computing revolution across continents.

Authors:

Quantinuum (alphabetical order): Eric Brunner, Steve Clark, Fabian Finger, Gabriel Greene-Diniz, Pranav Kalidindi, Alexander Koziell-Pipe, David Zsolt Manrique, Konstantinos Meichanetzidis, Frederic Rapp

Hiverge (alphabetical order): Alhussein Fawzi, Hamza Fawzi, Kerry He, Bernardino Romera Paredes, Kante Yin

What if every quantum computing researcher had an army of students to help them write efficient quantum algorithms? Large Language Models are starting to serve as such a resource.

Quantinuum’s processors offer world-leading fidelity, and recent experiments show that they have surpassed the limits of classical simulation for certain computational tasks, such as simulating materials. However, access to quantum processors is limited and can be costly. It is therefore of paramount importance to optimise quantum resources and write efficient quantum software. Designing efficient algorithms is a challenging task, especially for quantum algorithms: dealing with superpositions, entanglement, and interference can be counterintuitive.

To this end, our joint team used Hiverge’s AI platform for automated algorithm discovery, the Hive, to probe the limits of what can be done in quantum chemistry. The Hive generates optimised algorithms tailored to a given problem, expressed in a familiar programming language, like Python. Thus, the Hive’s outputs allow for increased interpretability, enabling domain experts to potentially learn novel techniques from the AI-discovered solutions. Such AI-assisted workflows lower the barrier of entry for non-domain experts, as an initial sketch of an algorithmic idea suffices to achieve state-of-the-art solutions.

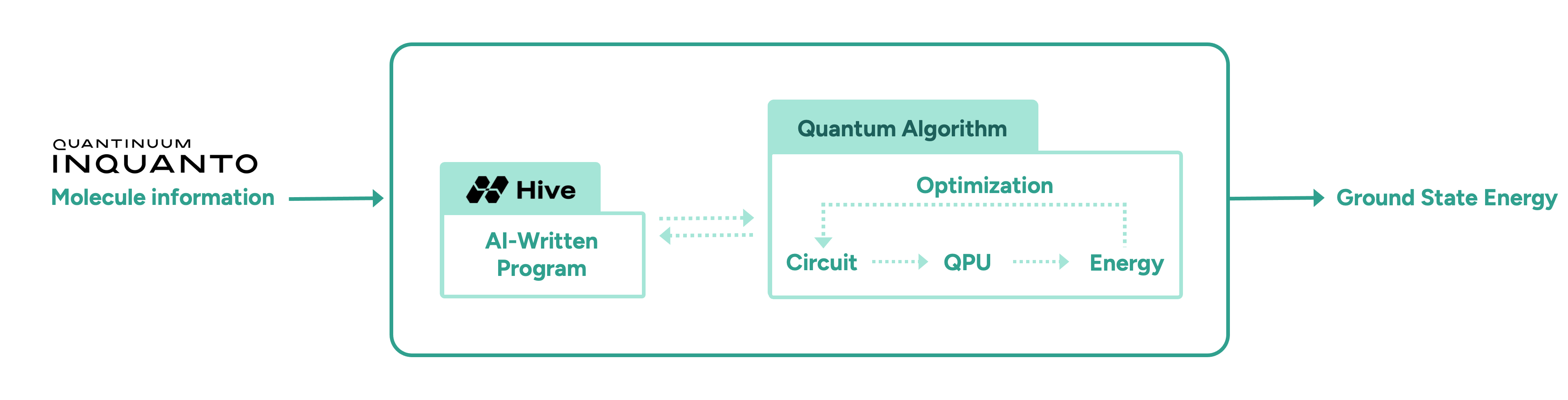

In this initial proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate the advantage of AI-driven algorithmic discovery of efficient quantum heuristics in the context of quantum chemistry, in particular the electronic structure problem. Our early explorations show that the Hive can start from a naïve and simple problem statement and evolve a highly optimised quantum algorithm that solves the problem, reaching chemical precision for a collection of molecules. Our high-level workflow is shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the quantum algorithm generated by the Hive achieves a reduction in the quantum resources required by orders of magnitude compared to current state-of-the-art quantum algorithms. This promising result may enable the implementation of quantum algorithms on near-term hardware that was previously thought impossible due to current resource constraints.

The Electronic Structure Problem in Quantum Chemistry

The electronic structure problem is central to quantum chemistry. The goal is to prepare the ground state (the lowest energy state) of a molecule and compute the corresponding energy of that state to chemical precision or beyond. Classically, this is an exponentially hard problem. In particular, classical treatments tend to fall short when there are strong quantum effects in the molecule, and this is where quantum computers may be advantageous.

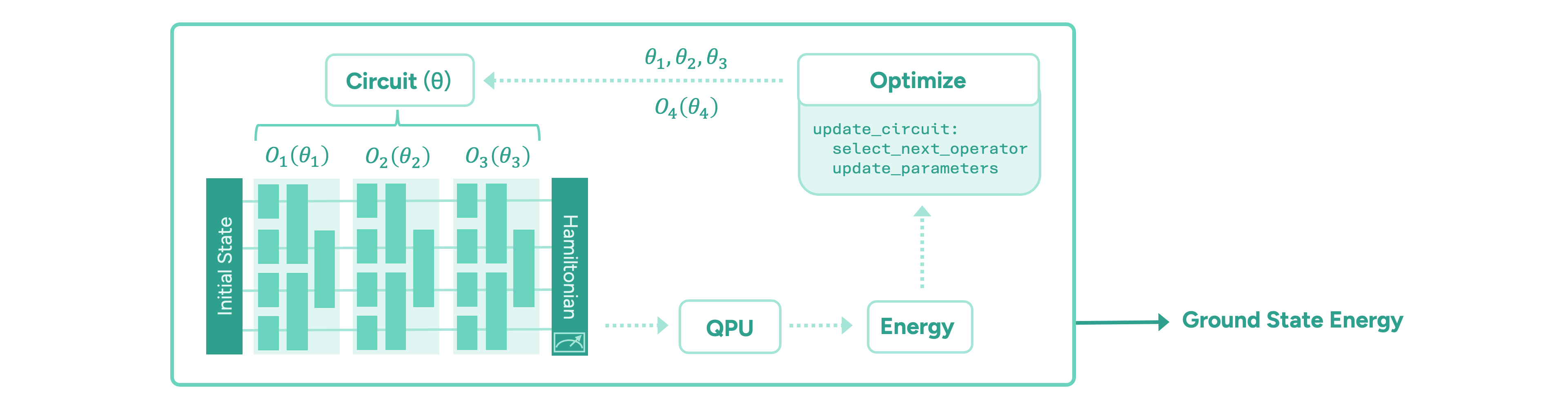

The paradigm of variational quantum algorithms is motivated by near-term quantum hardware. One starts with a relatively easy-to-prepare initial state. Then, the main part of the algorithm consists of a sequence of parameterised operators representing chemically meaningful actions, such as manipulating electron occupations in the molecular orbitals. These are implemented in terms of parameterised quantum gates. Finally, the energy of the state is measured via the molecule’s energy operator, the “Hamiltonian”, by executing the circuit on a quantum computer and measuring all the qubits on which the circuit is implemented. Taking many measurements, or “shots”, the energy is estimated to the desired precision. The ground state energy is found by iteratively optimising the parameters of the quantum circuit until the energy converges to a minimum value. The general form of such a variational quantum algorithm is illustrated in Figure 2.

The main challenge in these frameworks is to design an appropriate quantum circuit architecture, i.e. find an efficient sequence of operators, and an efficient optimisation strategy for its parameters. It is important to minimise the number of quantum operations in any given circuit, as each operation is inherently noisy and the algorithm’s output degrades exponentially. Another important quantum resource to be minimised is the total number of circuits that need to be evaluated to compute the energy values during the optimisation of the circuit parameters, which is time-consuming.

To meet these challenges, we task the Hive with designing a variational quantum algorithm to solve the ground state problem, following the workflow shown in Figure 1. The Hive is a distributed evolutionary process that evolves programs. It uses Large Language Models to generate mutations in the form of edits to an entire codebase. This genetic process selects the fittest programs according to how well they solve a given problem. In our case, the role of the quantum computer is to compute the fitness, i.e., the ground state energy. Importantly, the Hive operates at the level of a programming language; it readily imports and uses all known libraries that a human researcher would use, including Quantinuum’s quantum chemistry platform, InQuanto. In addition, the Hive can accept instructions and requests in natural language, increasing its flexibility. For example, we encouraged it to seek parameter optimisation strategies that avoid estimating gradients, as this incurs significant overhead in terms of circuit evaluations. Intuitively, the interaction between a human scientist and the Hive is analogous to a supervisor and a group of eager and capable students: the supervisor provides guidance at a high level, and the students collaborate and flesh out the general idea to produce a working solution that the supervisor can then inspect.

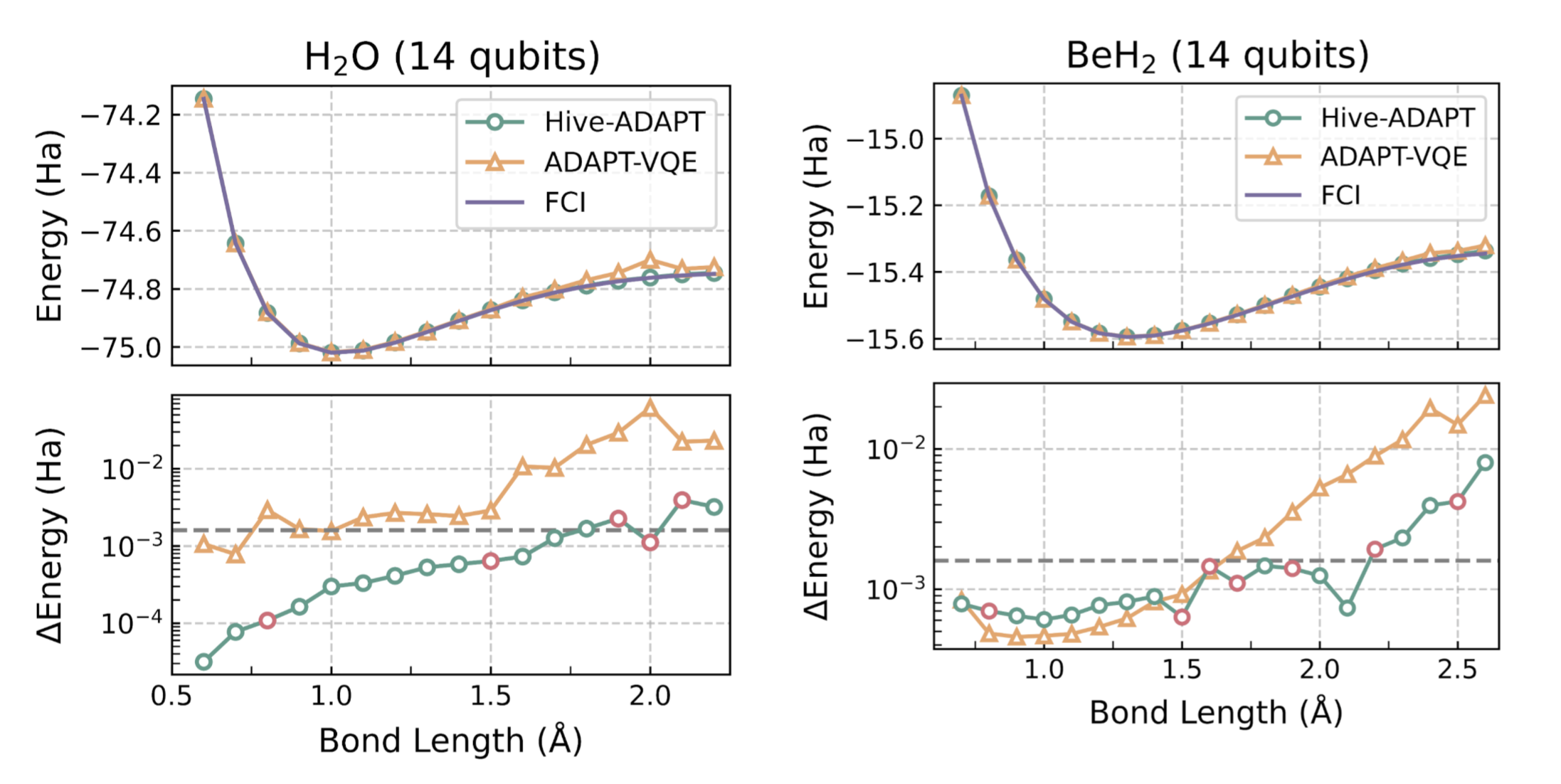

We find that from an extremely basic starting point, consisting of a skeleton for a variational quantum algorithm, the Hive can autonomously assemble a bespoke variational quantum algorithm, which we call Hive-ADAPT. Specifically, the Hive evolves heuristic functions that construct a circuit as a sequence of quantum operators and optimise its parameters. Remarkably, the Hive converged on a structure resembling the current state-of-the-art, ADAPT-VQE. Crucially, however, Hive-ADAPT substantially outperforms this baseline, delivering significant improvements in chemical precision while reducing quantum resource requirements.

A molecule’s ground state energy varies with the distances between its atoms, called the “bond length”. For example, for the molecule H2O, the bond length refers to the length of the O-H bond. The Hive was tasked with developing an algorithm for a small set of bond lengths and reaching chemical precision, defined as within 1.6e-3 Hartree (Ha) of the ground state energy computed with the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) algorithm. As we show in Figure 3, remarkably, Hive-ADAPT achieves chemical precision for more bond lengths than ADAPT-VQE. Furthermore, Hive-ADAPT also reaches chemical precision for other “unseen” bond lengths, showcasing the generalisation ability of the evolved quantum algorithm. Our results were obtained from classical simulations of the quantum algorithms, where we used NVIDIA CUDA-Q to leverage the parallelism enabled by GPUs. Further, relative to ADAPT-VQE, Hive-ADAPT exhibits one to two orders of magnitude reduction in quantum resources, such as the number of circuit evaluations and the number of operators used to construct circuits, which is crucial for practical implementations on actual near-term processors.

For molecules such as BeH2 at large Be-H bond lengths, a complex initial state is required for the algorithm to be able to reach the ground state using the available operators. Even in these cases, by leveraging an efficient state preparation scheme implemented in InQuanto, the Hive evolved a dedicated strategy for the preparation of such a complex initial state, given a set of basic operators to achieve the desired chemical precision.

To validate Hive-ADAPT under realistic conditions, we employed Quantinuum’s H2 Emulator, which provides a faithful classical simulator of the H2 quantum computer, characterised by a 1.05e-3 two-qubit gate error rate. Leveraging the Hive's inherent flexibility, we adapted the optimisation strategy to explicitly penalise the number of two-qubit gates—the dominant noise source on near-term hardware—by redefining the fitness function. This constraint guided the Hive to discover a noise-aware algorithm capable of constructing hardware-efficient circuits. We subsequently executed the specific circuit generated by this algorithm for the LiH molecule at a bond length of 1.5 Å with the Partition Measurement Symmetry Verification (PMSV) error mitigation procedure. The resulting energy of -7.8767 ± 0.0031 Ha, obtained using 10,000 shots per circuit with a discard rate below 10% in the PMSV error mitigation procedure, is close to the target FCI energy of -7.8824 Ha and demonstrates the Hive's ability to successfully tailor algorithms that balance theoretical accuracy with the rigorous constraints of hardware noise and approach chemical precision as much as possible with current quantum technology.

For illustration purposes, we show an example of an elaborate code snippet evolved by the Hive starting from a trivial version:

Quantinuum’s in-house quantum chemistry expert, Dr. David Zsolt Manrique, commented,

“I found it amazing that the Hive converged to a domain-expert level idea. By inspecting the code, we see it has identified the well-known perturbative method, ‘MP2’, as a useful guide; not only for setting the initial circuit parameters, but also for ordering excitations efficiently. Further, it systematically and laboriously fine-tuned those MP2-inspired heuristics over many iterations in a way that would be difficult for a human expert to do by hand. It demonstrated an impressive combination of domain expertise and automated machinery that would be useful in exploring novel quantum chemistry methods.”

Looking to the Future

In this initial proof-of-concept collaborative study between Quantinuum and Hiverge, we demonstrate that AI-driven algorithm discovery can generate efficient quantum heuristics. Specifically, we found a great reduction in quantum resources, which is impactful for quantum algorithmic primitives that are frequently reused. Importantly, this approach is highly flexible; it can accommodate the optimisation of any desired quantum resource, from circuit evaluations to the number of operations in a given circuit. This work opens a path toward fully automated pipelines capable of developing problem-specific quantum algorithms optimised for NISQ as well as future hardware.

An important question for further investigation regards transferability and generalisation of a discovered quantum solution to other molecules, going beyond the generalisation over bond lengths of the same molecule that we have already observed. Evidently, this approach can be applied to improving any other near-term quantum algorithm for a range of applications from optimisation to quantum simulation.

We have already demonstrated an error-corrected implementation of quantum phase estimation on quantum hardware, and an AI-driven approach promises further hardware-tailored improvements and optimal use of quantum resources. Beyond NISQ, we envision that AI-assisted algorithm discovery will be a fruitful endeavour in the fault-tolerant regime, as well, where high-level quantum algorithmic primitives (quantum fourier transform, amplitude amplification, quantum signal processing, etc.) are to be combined optimally to achieve computational advantage for certain problems.

Notably, we’ve entered an era where quantum algorithms can be written in high-level programming languages, like Quantinuum’s Guppy, and approaches that integrate Large Language Models directly benefit. Automated algorithm discovery is promising for improving routines relevant to the full quantum stack, for example, in low-level quantum control or in quantum error correction.

Quantinuum is focusing on redefining what’s possible in hybrid quantum–classical computing by integrating Quantinuum’s best-in-class systems with high-performance NVIDIA accelerated computing to create powerful new architectures that can solve the world’s most pressing challenges.

The launch of Helios, Powered by Honeywell, the world’s most accurate quantum computer, marks a major milestone in quantum computing. Helios is now available to all customers through the cloud or on-premise deployment, launched with a go-to-market offering that seamlessly pairs Helios with the NVIDIA Grace Blackwell platform, targeting specific end markets such as drug discovery, finance, materials science, and advanced AI research.

We are also working with NVIDIA to adopt NVIDIA NVQLink, an open system architecture, as a standard for advancing hybrid quantum-classical supercomputing. Using this technology with Quantinuum Guppy and the NVIDIA CUDA-Q platform, Quantinuum has implemented NVIDIA accelerated computing across Helios and future systems to perform real-time decoding for quantum error correction.

In an industry-first demonstration, an NVIDIA GPU-based decoder integrated in the Helios control engine improved the logical fidelity of quantum operations by more than 3% — a notable gain given Helios’ already exceptionally low error rate. These results demonstrate how integration with NVIDIA accelerated computing through NVQLink can directly enhance the accuracy and scalability of quantum computation.

This unique collaboration spans the full Quantinuum technology stack. Quantinuum’s next-generation software development environment allows users to interleave quantum and GPU-accelerated classical computations in a single workflow. Developers can build hybrid applications using tools such as NVIDIA CUDA-Q, NVIDIA CUDA-QX, and Quantinuum’s Guppy, to make advanced quantum programming accessible to a broad community of innovators.

The collaboration also reaches into applied research through the NVIDIA Accelerated Quantum Computing Research Center (NVAQC), where an NVIDIA GB200 NVL72 supercomputer can be paired with Quantinuum’s Helios to further drive hybrid quantum-GPU research, including the development of breakthrough quantum-enhanced AI applications.

A recent achievement illustrates this potential: The ADAPT-GQE framework, a transformer-based Generative Quantum AI (GenQAI) approach, uses a Generative AI model to efficiently synthesize circuits to prepare the ground state of a chemical system on a quantum computer. Developed by Quantinuum, NVIDIA, and a pharmaceutical industry leader—and leveraging NVIDIA CUDA-Q with GPU-accelerated methods—ADAPT-GQE achieved a 234x speed-up in generating training data for complex molecules. The team used the framework to explore imipramine, a molecule crucial to pharmaceutical development. The transformer was trained on imipramine conformers to synthesize ground state circuits at orders of magnitude faster than ADAPT-VQE, and the circuit produced by the transformer was run on Helios to prepare the ground state using InQuanto, Quantinuum's computational chemistry platform.

From collaborating on hardware and software integrations to GenQAI applications, the collaboration between Quantinuum and NVIDIA is building the bridge between classical and quantum computing and creating a future where AI becomes more expansive through quantum computing, and quantum computing becomes more powerful through AI.

By Dr. Noah Berthusen

The earliest works on quantum error correction showed that by combining many noisy physical qubits into a complex entangled state called a "logical qubit," this state could survive for arbitrarily long times. QEC researchers devote much effort to hunt for codes that function well as "quantum memories," as they are called. Many promising code families have been found, but this is only half of the story.

Being able to keep a qubit around for a long time is one thing, but to realize the theoretical advantages of quantum computing we need to run quantum circuits. And to make sure noise doesn't ruin our computation, these circuits need to be run on the logical qubits of our code. This is often much more challenging than performing gates on the physical qubits of our device, as these "logical gates" often require many physical operations in their implementation. What's more, it often is not immediately obvious which logical gates a code has, and so converting a physical circuit into a logical circuit can be rather difficult.

Some codes, like the famous surface code, are good quantum memories and also have easy logical gates. The drawback is that the ratio of physical qubits to logical qubits (the "encoding rate") is low, and so many physical qubits are required to implement large logical algorithms. High-rate codes that are good quantum memories have also been found, but computing on them is much more difficult. The holy grail of QEC, so to speak, would be a high-rate code that is a good quantum memory and also has easy logical gates. Here, we make progress on that front by developing a new code with those properties.

Building on prior error correcting codes

A recent work from Quantinuum QEC researchers introduced genon codes. The underlying construction method for these codes, called the "symplectic double cover," also provided a way to obtain logical gates that are well suited for Quantinuum's QCCD architecture. Namely, these "SWAP-transversal" gates are performed by applying single qubit operations and relabeling the physical qubits of the device. Thanks to the all-to-all connectivity facilitated through qubit movement on the QCCD architecture, this relabeling can be done in software essentially for free. Combined with extremely high fidelity (~1.2 x10-5) single-qubit operations, the resulting logical gates are similarly high fidelity.

Given the promise of these codes, we take them a step further in our new paper. We combine the symplectic double codes with the [[4,2,2]] Iceberg code using a procedure called "code concatenation". A concatenated code is a bit like nesting dolls, with an outer code containing codes within it---with these too potentially containing codes. More technically, in a concatenated code the logical qubits of one code act as the physical qubits of another code.

The new codes, which we call "concatenated symplectic double codes", were designed in such a way that they have many of these easily-implementable SWAP-transversal gates. Central to its construction, we show how the concatenation method allows us to "upgrade" logical gates in terms of their ease of implementation; this procedure may provide insights for constructing other codes with convenient logical gates. Notably, the SWAP-transversal gate set on this code is so powerful that only two additional operations (logical T and S) are necessary for universal computation. Furthermore, these codes have many logical qubits, and we also present numerical evidence to suggest that they are good quantum memories.

Concatenated symplectic double codes have one of the easiest logical computation schemes, and we didn’t have to sacrifice rate to achieve it. Looking forward in our roadmap, we are targeting hundreds of logical qubits at ~ 1x 10-8 logical error rate by 2029. These codes put us in a prime position to leverage the best characteristics of our hardware and create a device that can achieve real commercial advantage.