Technical perspective: By the end of the decade, we will deliver universal, fully fault-tolerant quantum computing

By Dr. Harry Buhrman, Chief Scientist for Algorithms and Innovation, and Dr. Chris Langer, Fellow

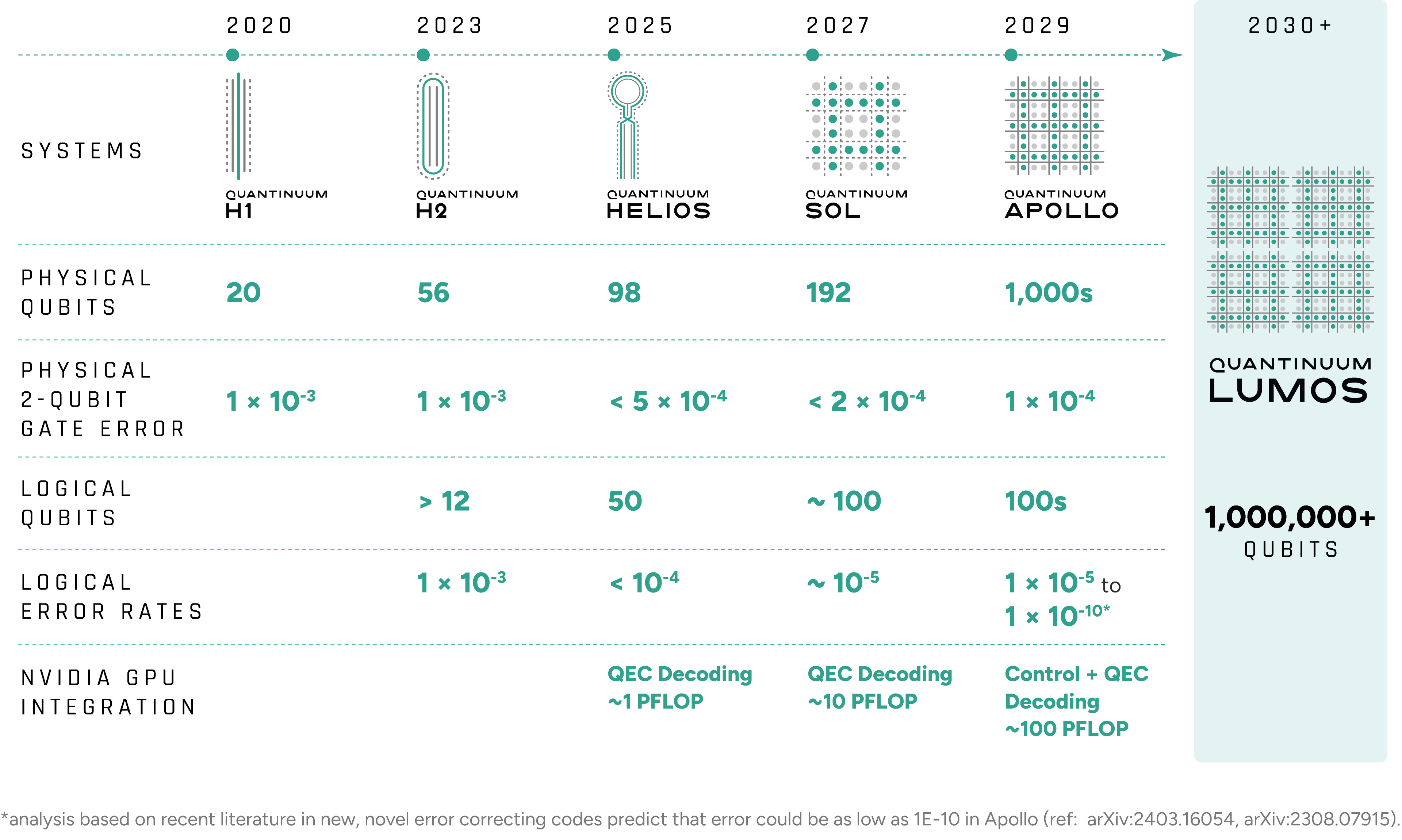

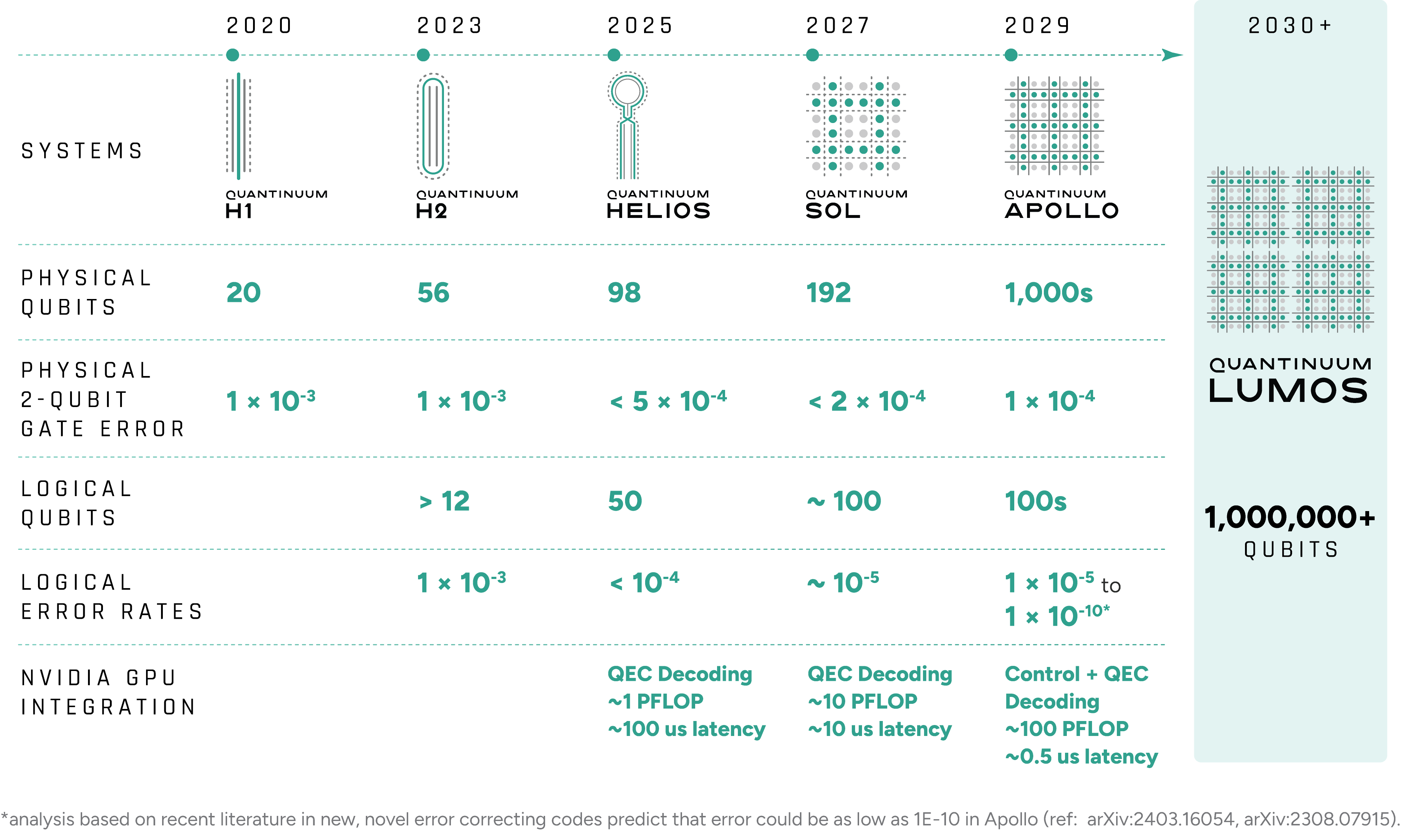

This week, we confirm what has been implied by the rapid pace of our recent technical progress as we reveal a major acceleration in our hardware road map. By the end of the decade, our accelerated hardware roadmap will deliver a fully fault-tolerant and universal quantum computer capable of executing millions of operations on hundreds of logical qubits.

The next major milestone on our accelerated roadmap is Quantinuum Helios™, Powered by Honeywell, a device that will definitively push beyond classical capabilities in 2025. That sets us on a path to our fifth-generation system, Quantinuum Apollo™, a machine that delivers scientific advantage and a commercial tipping point this decade.

Note: Helios was launched with 2 more qubits than initially planned, bringing the total to 98.

What is Apollo?

We are committed to continually advancing the capabilities of our hardware over prior generations, and Apollo makes good on that promise. It will offer:

- Thousands of physical qubits

- Physical error rate of 10-4

- All of our most competitive features: all-to-all connectivity, low crosstalk, mid-circuit measurement and qubit re-use

- Conditional logic

- Real-time classical co-compute

- Physical variable angle 1 qubit and 2 qubit gates

- Hundreds of logical qubits

- Logical error rates better than 10-6 with analysis based on recent literature estimating as low as 10-10

By leveraging our all-to-all connectivity and low error rates, we expect to enjoy significant efficiency gains in terms of fault-tolerance, including single-shot error correction (which saves time) and high-rate and high-distance Quantum Error Correction (QEC) codes (which mean more logical qubits, with stronger error correction capabilities, can be made from a smaller number of physical qubits).

Studies of several efficient QEC codes already suggest we can enjoy logical error rates much lower than our target 10-6 – we may even be able to reach 10-10, which enables exploration of even more complex problems of both industrial and scientific interest.

Error correcting code exploration is only just beginning – we anticipate discoveries of even more efficient codes. As new codes are developed, Apollo will be able to accommodate them, thanks to our flexible high-fidelity architecture. The bottom line is that Apollo promises fault-tolerant quantum advantage sooner, with fewer resources.

Like all our computers, Apollo is based on the quantum charged coupled device (QCCD) architecture. Here, each qubit’s information is stored in the atomic states of a single ion. Laser beams are applied to the qubits to perform operations such as gates, initialization, and measurement. The lasers are applied to individual qubits or co-located qubit pairs in dedicated operation zones. Qubits are held in place using electromagnetic fields generated by our ion trap chip. We move the qubits around in space by dynamically changing the voltages applied to the chip. Through an alternating sequence of qubit rearrangements via movement followed by quantum operations, arbitrary circuits with arbitrary connectivity can be executed.

The ion trap chip in Apollo will host a 2D array of trapping locations. It will be fabricated using standard CMOS processing technology and controlled using standard CMOS electronics. The 2D grid architecture enables fast and scalable qubit rearrangement and quantum operations – a critical competitive advantage. The Apollo architecture is scalable to the significantly larger systems we plan to deliver in the next decade.

What is Apollo good for?

Apollo’s scaling of very stable physical qubits and native high-fidelity gates, together with our advanced error correcting and fault tolerant techniques will establish a quantum computer that can perform tasks that do not run (efficiently) on any classical computer. We already had a first glimpse of this in our recent work sampling the output of random quantum circuits on H2, where we performed 100x better than competitors who performed the same task while using 30,000x less power than a classical supercomputer. But with Apollo we will travel into uncharted territory.

The flexibility to use either thousands of qubits for shorter computations (up to 10k gates) or hundreds of qubits for longer computations (from 1 million to 1 billion gates) make Apollo a versatile machine with unprecedented quantum computational power. We expect the first application areas will be in scientific discovery; particularly the simulation of quantum systems. While this may sound academic, this is how all new material discovery begins and its value should not be understated. This era will lead to discoveries in materials science, high-temperature superconductivity, complex magnetic systems, phase transitions, and high energy physics, among other things.

In general, Apollo will advance the field of physics to new heights while we start to see the first glimmers of distinct progress in chemistry and biology. For some of these applications, users will employ Apollo in a mode where it offers thousands of qubits for relatively short computations; e.g. exploring the magnetism of materials. At other times, users may want to employ significantly longer computations for applications like chemistry or topological data analysis.

But there is more on the horizon. Carefully crafted AI models that interact seamlessly with Apollo will be able to squeeze all the “quantum juice” out and generate data that was hitherto unavailable to mankind. We anticipate using this data to further the field of AI itself, as it can be used as training data.

The era of scientific (quantum) discovery and exploration will inevitably lead to commercial value. Apollo will be the centerpiece of this commercial tipping point where use-cases will build on the value of scientific discovery and support highly innovative commercially viable products.

Very interestingly, we will uncover applications that we are currently unaware of. As is always the case with disruptive new technology, Apollo will run currently unknown use-cases and applications that will make perfect sense once we see them. We are eager to co-develop these with our customers in our unique co-creation program.

How do we get there?

Today, System Model H2 is our most advanced commercial quantum computer, providing 56 physical qubits with physical two-qubit gate errors less than 10-3. System Model H2, like all our systems, is based on the QCCD architecture.

Starting from where we are today, our roadmap progresses through two additional machines prior to Apollo. The Quantinuum Helios™ system, which we are releasing in 2025, will offer around 100 physical qubits with two-qubit gate errors less than 5x10-4. In addition to expanded qubit count and better errors, Helios makes two departures from H2. First, Helios will use 137Ba+ qubits in contrast to the 171Yb+ qubits used in our H1 and H2 systems. This change enables lower two-qubit gate errors and less complex laser systems with lower cost. Second, for the first time in a commercial system, Helios will use junction-based qubit routing. The result will be a “twice-as-good" system: Helios will offer roughly 2x more qubits with 2x lower two-qubit gate errors while operating more than 2x faster than our 56-qubit H2 system.

After Helios we will introduce Quantinuum Sol™, our first commercially available 2D-grid-based quantum computer. Sol will offer hundreds of physical qubits with two-qubit gate errors less than 2x10-4, operating approximately 2x faster than Helios. Sol being a fully 2D-grid architecture is the scalability launching point for the significant size increase planned for Apollo.

Opportunity for early value creation discovery in Helios and Sol

Thanks to Sol’s low error rates, users will be able to execute circuits with up to 10,000 quantum operations. The usefulness of Helios and Sol may be extended with a combination of quantum error detection (QED) and quantum error mitigation (QEM). For example, the [[k+2, k, 2]] iceberg code is a light-weight QED code that encodes k+2 physical qubits into k logical qubits and only uses an additional 2 ancilla qubits. This low-overhead code is well-suited for Helios and Sol because it offers the non-Clifford variable angle entangling ZZ-gate directly without the overhead of magic state distillation. The errors Iceberg fails to detect are already ~10x lower than our physical errors, and by applying a modest run-time overhead to discard detected failures, the effective error in the computation can be further reduced. Combining QED with QEM, a ~10x reduction in the effective error may be possible while maintaining run-time overhead at modest levels and below that of full-blown QEC.

Why accelerate our roadmap now?

Our new roadmap is an acceleration over what we were previously planning. The benefits of this are obvious: Apollo brings the commercial tipping point sooner than we previously thought possible. This acceleration is made possible by a set of recent breakthroughs.

First, we solved the “wiring problem”: we demonstrated that trap chip control is scalable using our novel center-to-left-right (C2LR) protocol and broadcasting shared control signals to multiple electrodes. This demonstration of qubit rearrangement in a 2D geometry marks the most advanced ion trap built, containing approximately 40 junctions. This trap was deployed to 3 different testbeds in 2 different cities and operated with 2 different collections of dual-ion-species, and all 3 cases were a success. These demonstrations showed that the footprint of the most complex parts of the trap control stay constant as the number of qubits scales up. This gives us the confidence that Sol, with approximately 100 junctions, will be a success.

Second, we continue to reduce our two-qubit physical gate errors. Today, H1 and H2 have two-qubit gate errors less than 1x10-3 across all pairs of qubits. This is the best in the industry and is a key ingredient in our record >2 million quantum volume. Our systems are the most benchmarked in the industry, and we stand by our data - making it all publicly available. Recently, we observed an 8x10-4 two-qubit gate error in our Helios development test stand in 137Ba+, and we’ve seen even better error rates in other testbeds. We are well on the path to meeting the 5x10-4 spec in Helios next year.

Third, the all-to-all connectivity offered by our systems enables highly efficient QEC codes. In Microsoft’s recent demonstration, our H2 system with 56 physical qubits was used to generate 12 logical qubits at distance 4. This work demonstrated several experiments, including repeated rounds of error correction where the error in the final result was ~10x lower than the physical circuit baseline.

In conclusion, through a combination of advances in hardware readiness and QEC, we have line-of-sight to Apollo by the end of the decade, a fully fault-tolerant quantum advantaged machine. This will be a commercial tipping point: ushering in an era of scientific discovery in physics, materials, chemistry, and more. Along the way, users will have the opportunity to discover new enabling use cases through quantum error detection and mitigation in Helios and Sol.

Quantinuum has the best quantum computers today and is on the path to offering fault-tolerant useful quantum computation by the end of the decade.

About Quantinuum

Quantinuum, the world’s largest integrated quantum company, pioneers powerful quantum computers and advanced software solutions. Quantinuum’s technology drives breakthroughs in materials discovery, cybersecurity, and next-gen quantum AI. With over 500 employees, including 370+ scientists and engineers, Quantinuum leads the quantum computing revolution across continents.

Authors:

Quantinuum (alphabetical order): Eric Brunner, Steve Clark, Fabian Finger, Gabriel Greene-Diniz, Pranav Kalidindi, Alexander Koziell-Pipe, David Zsolt Manrique, Konstantinos Meichanetzidis, Frederic Rapp

Hiverge (alphabetical order): Alhussein Fawzi, Hamza Fawzi, Kerry He, Bernardino Romera Paredes, Kante Yin

What if every quantum computing researcher had an army of students to help them write efficient quantum algorithms? Large Language Models are starting to serve as such a resource.

Quantinuum’s processors offer world-leading fidelity, and recent experiments show that they have surpassed the limits of classical simulation for certain computational tasks, such as simulating materials. However, access to quantum processors is limited and can be costly. It is therefore of paramount importance to optimise quantum resources and write efficient quantum software. Designing efficient algorithms is a challenging task, especially for quantum algorithms: dealing with superpositions, entanglement, and interference can be counterintuitive.

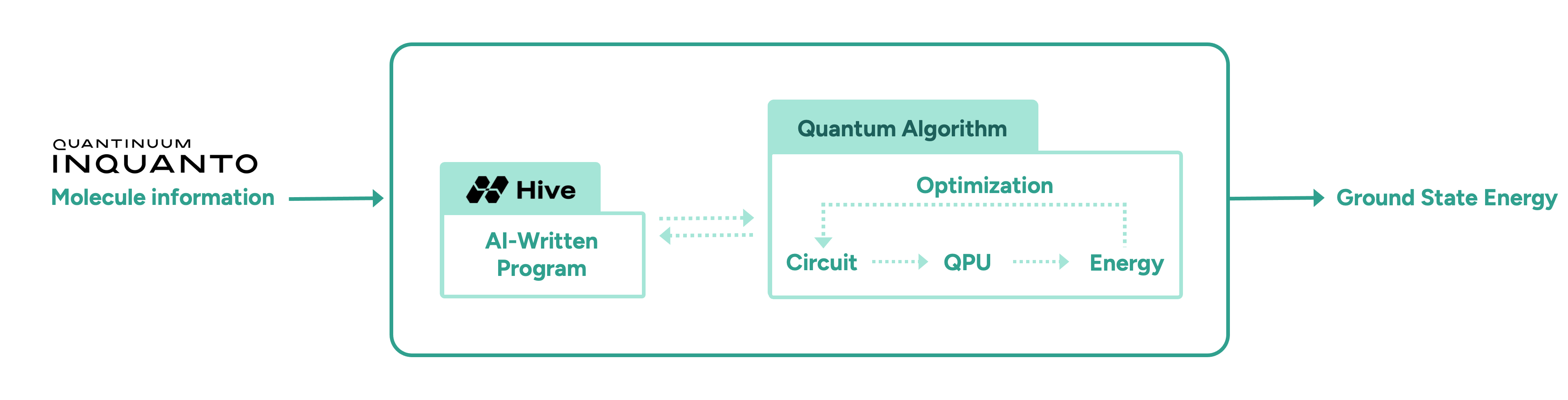

To this end, our joint team used Hiverge’s AI platform for automated algorithm discovery, the Hive, to probe the limits of what can be done in quantum chemistry. The Hive generates optimised algorithms tailored to a given problem, expressed in a familiar programming language, like Python. Thus, the Hive’s outputs allow for increased interpretability, enabling domain experts to potentially learn novel techniques from the AI-discovered solutions. Such AI-assisted workflows lower the barrier of entry for non-domain experts, as an initial sketch of an algorithmic idea suffices to achieve state-of-the-art solutions.

In this initial proof-of-concept study, we demonstrate the advantage of AI-driven algorithmic discovery of efficient quantum heuristics in the context of quantum chemistry, in particular the electronic structure problem. Our early explorations show that the Hive can start from a naïve and simple problem statement and evolve a highly optimised quantum algorithm that solves the problem, reaching chemical precision for a collection of molecules. Our high-level workflow is shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the quantum algorithm generated by the Hive achieves a reduction in the quantum resources required by orders of magnitude compared to current state-of-the-art quantum algorithms. This promising result may enable the implementation of quantum algorithms on near-term hardware that was previously thought impossible due to current resource constraints.

The Electronic Structure Problem in Quantum Chemistry

The electronic structure problem is central to quantum chemistry. The goal is to prepare the ground state (the lowest energy state) of a molecule and compute the corresponding energy of that state to chemical precision or beyond. Classically, this is an exponentially hard problem. In particular, classical treatments tend to fall short when there are strong quantum effects in the molecule, and this is where quantum computers may be advantageous.

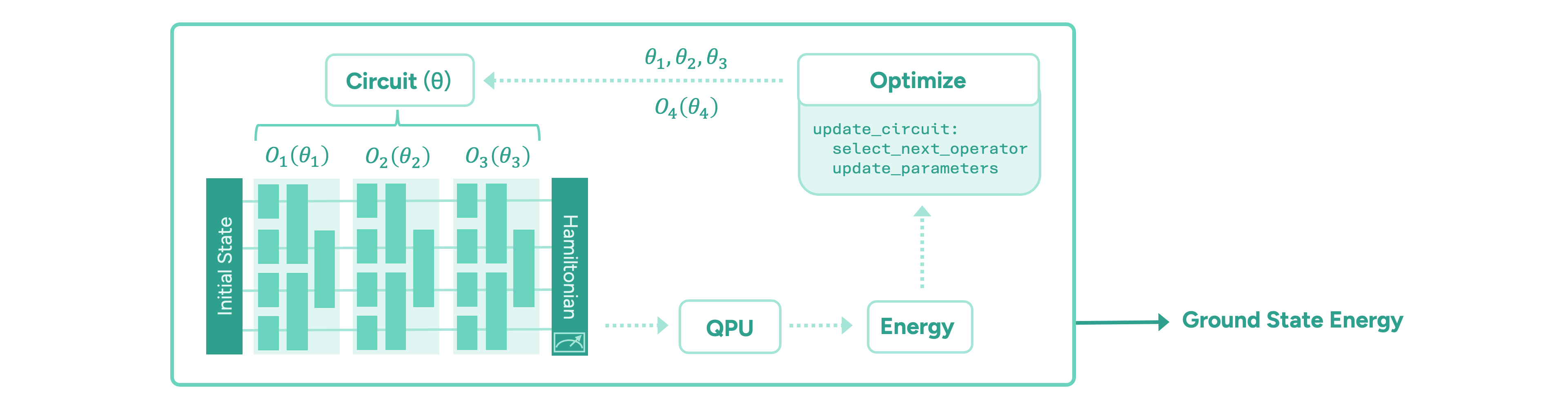

The paradigm of variational quantum algorithms is motivated by near-term quantum hardware. One starts with a relatively easy-to-prepare initial state. Then, the main part of the algorithm consists of a sequence of parameterised operators representing chemically meaningful actions, such as manipulating electron occupations in the molecular orbitals. These are implemented in terms of parameterised quantum gates. Finally, the energy of the state is measured via the molecule’s energy operator, the “Hamiltonian”, by executing the circuit on a quantum computer and measuring all the qubits on which the circuit is implemented. Taking many measurements, or “shots”, the energy is estimated to the desired precision. The ground state energy is found by iteratively optimising the parameters of the quantum circuit until the energy converges to a minimum value. The general form of such a variational quantum algorithm is illustrated in Figure 2.

The main challenge in these frameworks is to design an appropriate quantum circuit architecture, i.e. find an efficient sequence of operators, and an efficient optimisation strategy for its parameters. It is important to minimise the number of quantum operations in any given circuit, as each operation is inherently noisy and the algorithm’s output degrades exponentially. Another important quantum resource to be minimised is the total number of circuits that need to be evaluated to compute the energy values during the optimisation of the circuit parameters, which is time-consuming.

To meet these challenges, we task the Hive with designing a variational quantum algorithm to solve the ground state problem, following the workflow shown in Figure 1. The Hive is a distributed evolutionary process that evolves programs. It uses Large Language Models to generate mutations in the form of edits to an entire codebase. This genetic process selects the fittest programs according to how well they solve a given problem. In our case, the role of the quantum computer is to compute the fitness, i.e., the ground state energy. Importantly, the Hive operates at the level of a programming language; it readily imports and uses all known libraries that a human researcher would use, including Quantinuum’s quantum chemistry platform, InQuanto. In addition, the Hive can accept instructions and requests in natural language, increasing its flexibility. For example, we encouraged it to seek parameter optimisation strategies that avoid estimating gradients, as this incurs significant overhead in terms of circuit evaluations. Intuitively, the interaction between a human scientist and the Hive is analogous to a supervisor and a group of eager and capable students: the supervisor provides guidance at a high level, and the students collaborate and flesh out the general idea to produce a working solution that the supervisor can then inspect.

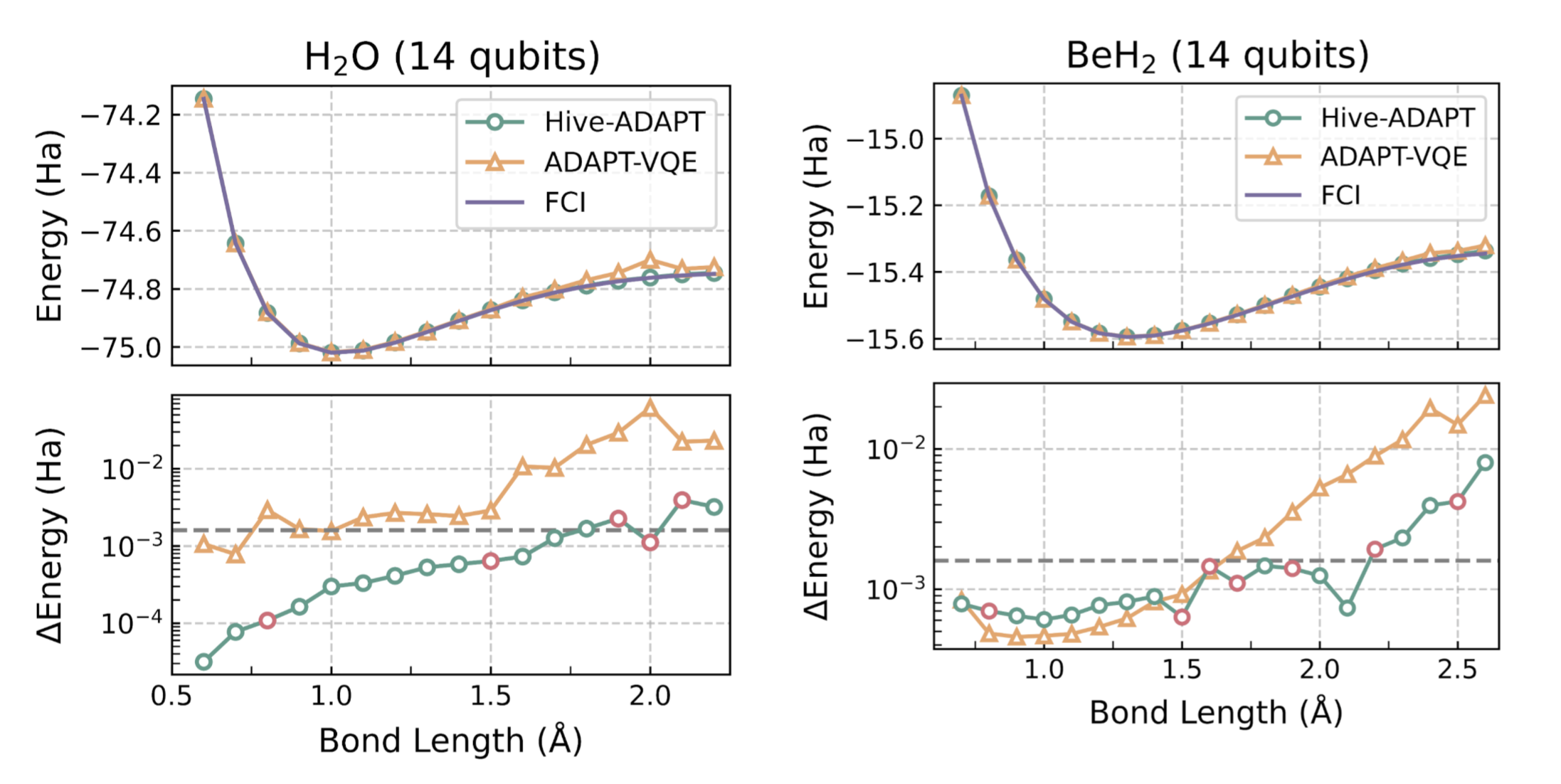

We find that from an extremely basic starting point, consisting of a skeleton for a variational quantum algorithm, the Hive can autonomously assemble a bespoke variational quantum algorithm, which we call Hive-ADAPT. Specifically, the Hive evolves heuristic functions that construct a circuit as a sequence of quantum operators and optimise its parameters. Remarkably, the Hive converged on a structure resembling the current state-of-the-art, ADAPT-VQE. Crucially, however, Hive-ADAPT substantially outperforms this baseline, delivering significant improvements in chemical precision while reducing quantum resource requirements.

A molecule’s ground state energy varies with the distances between its atoms, called the “bond length”. For example, for the molecule H2O, the bond length refers to the length of the O-H bond. The Hive was tasked with developing an algorithm for a small set of bond lengths and reaching chemical precision, defined as within 1.6e-3 Hartree (Ha) of the ground state energy computed with the exact Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) algorithm. As we show in Figure 3, remarkably, Hive-ADAPT achieves chemical precision for more bond lengths than ADAPT-VQE. Furthermore, Hive-ADAPT also reaches chemical precision for other “unseen” bond lengths, showcasing the generalisation ability of the evolved quantum algorithm. Our results were obtained from classical simulations of the quantum algorithms, where we used NVIDIA CUDA-Q to leverage the parallelism enabled by GPUs. Further, relative to ADAPT-VQE, Hive-ADAPT exhibits one to two orders of magnitude reduction in quantum resources, such as the number of circuit evaluations and the number of operators used to construct circuits, which is crucial for practical implementations on actual near-term processors.

For molecules such as BeH2 at large Be-H bond lengths, a complex initial state is required for the algorithm to be able to reach the ground state using the available operators. Even in these cases, by leveraging an efficient state preparation scheme implemented in InQuanto, the Hive evolved a dedicated strategy for the preparation of such a complex initial state, given a set of basic operators to achieve the desired chemical precision.

To validate Hive-ADAPT under realistic conditions, we employed Quantinuum’s H2 Emulator, which provides a faithful classical simulator of the H2 quantum computer, characterised by a 1.05e-3 two-qubit gate error rate. Leveraging the Hive's inherent flexibility, we adapted the optimisation strategy to explicitly penalise the number of two-qubit gates—the dominant noise source on near-term hardware—by redefining the fitness function. This constraint guided the Hive to discover a noise-aware algorithm capable of constructing hardware-efficient circuits. We subsequently executed the specific circuit generated by this algorithm for the LiH molecule at a bond length of 1.5 Å with the Partition Measurement Symmetry Verification (PMSV) error mitigation procedure. The resulting energy of -7.8767 ± 0.0031 Ha, obtained using 10,000 shots per circuit with a discard rate below 10% in the PMSV error mitigation procedure, is close to the target FCI energy of -7.8824 Ha and demonstrates the Hive's ability to successfully tailor algorithms that balance theoretical accuracy with the rigorous constraints of hardware noise and approach chemical precision as much as possible with current quantum technology.

For illustration purposes, we show an example of an elaborate code snippet evolved by the Hive starting from a trivial version:

Quantinuum’s in-house quantum chemistry expert, Dr. David Zsolt Manrique, commented,

“I found it amazing that the Hive converged to a domain-expert level idea. By inspecting the code, we see it has identified the well-known perturbative method, ‘MP2’, as a useful guide; not only for setting the initial circuit parameters, but also for ordering excitations efficiently. Further, it systematically and laboriously fine-tuned those MP2-inspired heuristics over many iterations in a way that would be difficult for a human expert to do by hand. It demonstrated an impressive combination of domain expertise and automated machinery that would be useful in exploring novel quantum chemistry methods.”

Looking to the Future

In this initial proof-of-concept collaborative study between Quantinuum and Hiverge, we demonstrate that AI-driven algorithm discovery can generate efficient quantum heuristics. Specifically, we found a great reduction in quantum resources, which is impactful for quantum algorithmic primitives that are frequently reused. Importantly, this approach is highly flexible; it can accommodate the optimisation of any desired quantum resource, from circuit evaluations to the number of operations in a given circuit. This work opens a path toward fully automated pipelines capable of developing problem-specific quantum algorithms optimised for NISQ as well as future hardware.

An important question for further investigation regards transferability and generalisation of a discovered quantum solution to other molecules, going beyond the generalisation over bond lengths of the same molecule that we have already observed. Evidently, this approach can be applied to improving any other near-term quantum algorithm for a range of applications from optimisation to quantum simulation.

We have already demonstrated an error-corrected implementation of quantum phase estimation on quantum hardware, and an AI-driven approach promises further hardware-tailored improvements and optimal use of quantum resources. Beyond NISQ, we envision that AI-assisted algorithm discovery will be a fruitful endeavour in the fault-tolerant regime, as well, where high-level quantum algorithmic primitives (quantum fourier transform, amplitude amplification, quantum signal processing, etc.) are to be combined optimally to achieve computational advantage for certain problems.

Notably, we’ve entered an era where quantum algorithms can be written in high-level programming languages, like Quantinuum’s Guppy, and approaches that integrate Large Language Models directly benefit. Automated algorithm discovery is promising for improving routines relevant to the full quantum stack, for example, in low-level quantum control or in quantum error correction.

Quantinuum is focusing on redefining what’s possible in hybrid quantum–classical computing by integrating Quantinuum’s best-in-class systems with high-performance NVIDIA accelerated computing to create powerful new architectures that can solve the world’s most pressing challenges.

The launch of Helios, Powered by Honeywell, the world’s most accurate quantum computer, marks a major milestone in quantum computing. Helios is now available to all customers through the cloud or on-premise deployment, launched with a go-to-market offering that seamlessly pairs Helios with the NVIDIA Grace Blackwell platform, targeting specific end markets such as drug discovery, finance, materials science, and advanced AI research.

We are also working with NVIDIA to adopt NVIDIA NVQLink, an open system architecture, as a standard for advancing hybrid quantum-classical supercomputing. Using this technology with Quantinuum Guppy and the NVIDIA CUDA-Q platform, Quantinuum has implemented NVIDIA accelerated computing across Helios and future systems to perform real-time decoding for quantum error correction.

In an industry-first demonstration, an NVIDIA GPU-based decoder integrated in the Helios control engine improved the logical fidelity of quantum operations by more than 3% — a notable gain given Helios’ already exceptionally low error rate. These results demonstrate how integration with NVIDIA accelerated computing through NVQLink can directly enhance the accuracy and scalability of quantum computation.

This unique collaboration spans the full Quantinuum technology stack. Quantinuum’s next-generation software development environment allows users to interleave quantum and GPU-accelerated classical computations in a single workflow. Developers can build hybrid applications using tools such as NVIDIA CUDA-Q, NVIDIA CUDA-QX, and Quantinuum’s Guppy, to make advanced quantum programming accessible to a broad community of innovators.

The collaboration also reaches into applied research through the NVIDIA Accelerated Quantum Computing Research Center (NVAQC), where an NVIDIA GB200 NVL72 supercomputer can be paired with Quantinuum’s Helios to further drive hybrid quantum-GPU research, including the development of breakthrough quantum-enhanced AI applications.

A recent achievement illustrates this potential: The ADAPT-GQE framework, a transformer-based Generative Quantum AI (GenQAI) approach, uses a Generative AI model to efficiently synthesize circuits to prepare the ground state of a chemical system on a quantum computer. Developed by Quantinuum, NVIDIA, and a pharmaceutical industry leader—and leveraging NVIDIA CUDA-Q with GPU-accelerated methods—ADAPT-GQE achieved a 234x speed-up in generating training data for complex molecules. The team used the framework to explore imipramine, a molecule crucial to pharmaceutical development. The transformer was trained on imipramine conformers to synthesize ground state circuits at orders of magnitude faster than ADAPT-VQE, and the circuit produced by the transformer was run on Helios to prepare the ground state using InQuanto, Quantinuum's computational chemistry platform.

From collaborating on hardware and software integrations to GenQAI applications, the collaboration between Quantinuum and NVIDIA is building the bridge between classical and quantum computing and creating a future where AI becomes more expansive through quantum computing, and quantum computing becomes more powerful through AI.

By Dr. Noah Berthusen

The earliest works on quantum error correction showed that by combining many noisy physical qubits into a complex entangled state called a "logical qubit," this state could survive for arbitrarily long times. QEC researchers devote much effort to hunt for codes that function well as "quantum memories," as they are called. Many promising code families have been found, but this is only half of the story.

Being able to keep a qubit around for a long time is one thing, but to realize the theoretical advantages of quantum computing we need to run quantum circuits. And to make sure noise doesn't ruin our computation, these circuits need to be run on the logical qubits of our code. This is often much more challenging than performing gates on the physical qubits of our device, as these "logical gates" often require many physical operations in their implementation. What's more, it often is not immediately obvious which logical gates a code has, and so converting a physical circuit into a logical circuit can be rather difficult.

Some codes, like the famous surface code, are good quantum memories and also have easy logical gates. The drawback is that the ratio of physical qubits to logical qubits (the "encoding rate") is low, and so many physical qubits are required to implement large logical algorithms. High-rate codes that are good quantum memories have also been found, but computing on them is much more difficult. The holy grail of QEC, so to speak, would be a high-rate code that is a good quantum memory and also has easy logical gates. Here, we make progress on that front by developing a new code with those properties.

Building on prior error correcting codes

A recent work from Quantinuum QEC researchers introduced genon codes. The underlying construction method for these codes, called the "symplectic double cover," also provided a way to obtain logical gates that are well suited for Quantinuum's QCCD architecture. Namely, these "SWAP-transversal" gates are performed by applying single qubit operations and relabeling the physical qubits of the device. Thanks to the all-to-all connectivity facilitated through qubit movement on the QCCD architecture, this relabeling can be done in software essentially for free. Combined with extremely high fidelity (~1.2 x10-5) single-qubit operations, the resulting logical gates are similarly high fidelity.

Given the promise of these codes, we take them a step further in our new paper. We combine the symplectic double codes with the [[4,2,2]] Iceberg code using a procedure called "code concatenation". A concatenated code is a bit like nesting dolls, with an outer code containing codes within it---with these too potentially containing codes. More technically, in a concatenated code the logical qubits of one code act as the physical qubits of another code.

The new codes, which we call "concatenated symplectic double codes", were designed in such a way that they have many of these easily-implementable SWAP-transversal gates. Central to its construction, we show how the concatenation method allows us to "upgrade" logical gates in terms of their ease of implementation; this procedure may provide insights for constructing other codes with convenient logical gates. Notably, the SWAP-transversal gate set on this code is so powerful that only two additional operations (logical T and S) are necessary for universal computation. Furthermore, these codes have many logical qubits, and we also present numerical evidence to suggest that they are good quantum memories.

Concatenated symplectic double codes have one of the easiest logical computation schemes, and we didn’t have to sacrifice rate to achieve it. Looking forward in our roadmap, we are targeting hundreds of logical qubits at ~ 1x 10-8 logical error rate by 2029. These codes put us in a prime position to leverage the best characteristics of our hardware and create a device that can achieve real commercial advantage.